University brewer Tomáš Gregor: Beer is a brilliant drink

Only sufficiently educated people with at least one year of brewing experience are allowed to establish their own brewery in the Czech Republic. In addition to beer enthusiasts who complete an accredited course, the students of the Faculty of AgriSciences at MENDELU are also able to become brewers. The Food Technologies study program teaches them about the fermenting industry which is the basis for the production of malt, essential materials for this golden concoction.

And this department is led by Tomáš Gregor, who knows pretty much all there is to know about beer, even though he claims one life isn’t enough to discover everything about this drink.

His journey to beer began when he, being only twelve years old, found a book from the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries at his grandparents’ house. He was intrigued by a recipe to produce beer from chicory, sugar beet, barley, and rye. “My grandparents used to drink chicory coffee, so I thought I’d give it a try. I added some yeast and a bit of non-cultivated hops growing nearby, put it all in a bottle, and let it ferment. A true poor farmer’s beer. I don’t remember any details, but I can only imagine how terrible it actually tasted,” recalls Gregor.

Nearly anything can be malted

You studied chemistry in high school and then focused on food technologies at university. In your habilitation thesis, you focused on beer and, specifically, on non-conventional materials used for the production of malt. What are beers made of sorghum or buckwheat like?

Classic lager-lovers wouldn’t be excited about them. Although people have begun to search for uncommon flavours lately, and the strong cereal taste in these beers provides just that. At the university, we regularly brew beer from quinoa which tastes just like a bread roll. Some people enjoy it, others don’t. Also, beers made from pseudocereals are gluten-free and contain a higher amount of soluble fibre.

Together with water and hops, malt is a basic material for the production of beer. It’s germinated and dried (or roasted) grain, most often barley. Malting creates enzymes in the grain that – during the production of beer – release simple saccharides from the grain and make it easier to ferment.

So these are healthier beers, right?

Of course, beer isn’t primarily meant to provide fibre for our bodies, but it’s an added value. This is also true about beer made from barley enriched with zinc or selenium; both minerals are hard for the body to absorb and few people have enough of them in their bodies, so it’s better to consume them in some food. Our colleagues at the Faculty of AgriScience came up with an idea to provide selenium directly to the plants, so it then gets into their grain and thus into malt and beer. It’s interesting to think that people could solve selenium deficiency issues by doing something they already like to do.

Are breweries interested in enlarging their range of products by using these non-conventional malts then?

Beer made from pseudocereals is produced for a very small range of people who feel like having something healthier or trying out new things. This is problematic because it hardly pays off for small breweries and big ones don’t like to experiment much, since they’d be risking their sales. When breweries do decide to do something less conventional, they add non-malted cereals to their beer which usually only add a bit of aroma.

Malting a non-conventional material isn’t a simple task, right?

There aren’t too many malting plants in our country: there are some big, industrial ones and some breweries run their own plants. Also, not a single malting plant has been established here for decades. Most often you’ll see wheat, barley, rye, or oats getting malted here, even to various degrees, but nobody ever malts pseudocereals.

It’s common practice for malting plants to have a minimum amount of five tons of grain, which makes around 20 thousand litres of beer. This means that in order to malt something unconventional, several small breweries would have to agree and divide the huge amount of malt among themselves. At our course, there was a man who wants to establish a small malting plant that would handle 100 to 500 kilograms of special kinds of malt.

The department operates its own micro-malting plant with a capacity of eight kilograms per batch. The malting process takes 10 days and produces enough malt to brew around 30 litres of beer. Of all the types of grain, Tomáš Gregor considers malting amaranth or millet to be the most unique. “The grains are so small that we had to put them into a stocking or they would fall right through the sieve. When sprouts appear, it looks like a brown hairy ball.” Anything that germinates can be malted, however, even apple seeds. “Beer made from apple seeds wouldn’t taste great, as apples contain a lot of tannins. However, if you bring apple seeds, I’ll be happy to malt them,” adds Gregor, smiling. One of his favourite creations was beer made from malted corn.

Gluten- and alcohol-free beer

However, beer made from pseudocereals would be an interesting gluten-free option. Aren’t breweries interested in it?

For gluten-free beer, breweries still use regular malt and just add enzymes that break down the substances that people suffering from Coeliac disease are sensitive to, so there’s no special malt required.

However, pseudocereals are good for producing non-alcoholic beer. Their enzymes are weaker and produce less fermentable substances – simple sugars – that could then be turned into alcohol. And the beer has a unique pseudocereal taste, which may be interesting for those who drink non-alcoholic beer.

How is beer brewed? There’s an infinite number of recipes and styles of beer, but they all share the same basic procedure:

Malt crushing: The malt gets crushed into small pieces to release substances that allow for fermentation and also provide flavour.

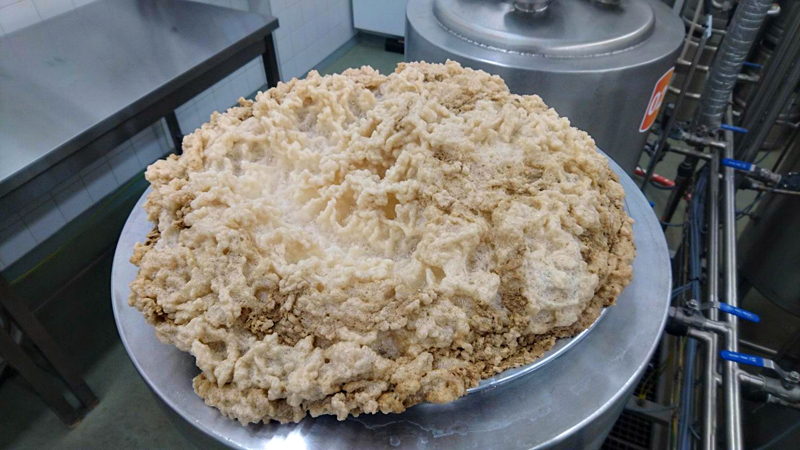

Mashing in the mash tun: The crushed malt is added into warm water and mixed.

Mashing: The mixture is heated, several times, depending on the type of beer, to create mash. The mash is then strained in a process known as lautering to create wort.

Copper/kettle: The wort is boiled with hops. The hops particles are removed in a “whirlpool”, and the hopped wort is cooled down and left to ferment.

Fermenting: The amount of sugar the yeast cells consume determines the richness of the beer and its alcohol content. At the end of the procedure, the beer is left to condition and age.

Has non-alcoholic beer become very popular in the Czech Republic as well? The first non-alcoholic beer bar just opened in London, but it isn’t as popular among Czech breweries yet.

Producing non-alcoholic beer is no easy task. According to the Czech law, the volume of alcohol in regular beer stated on the bottle may be actually 0.5% higher or lower, which is quite a range and it’s easy to observe it when you follow the recipe.

With non-alcoholic beer, the maximum permitted volume of alcohol is 0.5%, which makes it more demanding. Small breweries in particular rarely have laboratories or devices for measuring alcohol content so precisely, so even if they follow a recipe, there’s still a lot of risk involved.

At the university, we created a template for small breweries on how to brew non-alcoholic beer, so we believe that some breweries will work with us to add it to their offering.

Non-alcoholic beer typically starts out as a low-degree wort with the least possible amount of fermentable sugars. When it reaches 0.4% alcohol content, fermentation is stopped and the beer gets pasteurized. The yeast cells get killed to prevent further fermenting, for example in a bottle. However, the taste of the beer is weaker, as only one third of the usual amount of malt is used for the production of non-alcoholic beer.

Another way to produce non-alcoholic beer is to brew regular lager and distil the alcohol from it using a vacuum. “However, since alcohol carries the fullness of the taste, removing it leaves the beer “empty”, though still fuller than non-alcoholic beer made from four-degree wort. Non-alcoholic beer with a full taste is, in fact, possible through applied biochemistry; the composition of the beer would have to be analysed and enriched with some substances to ensure there are full tones in its taste. However, this is basically impossible to implement in regular brewing processes,” adds Gregor.

Are students interested in non-alcoholic beer?

A lot of final papers deal with non-alcoholic beer made from non-conventional materials, such as why there’s no dark non-alcoholic beer on our market. In the Brewing seminar, students always come up with a special kind of beer, but only rarely is it non-alcoholic. I like to motivate them to give it a try, as it’s quite a challenge. Mostly, though, they want to produce a strong type of beer. They just want to know that it’s “real beer” they are drinking.

In their research papers, students deal with a number of other issues related to beer, such as the use of yeast cell stems, the relationships between hops varieties and specific types of beer, and sensorics of hops as well as the pseudocereals. The students also brew beer at home. “Less-confident home brewers start with top-fermented beers and gradually make their way to lager. I’ve tasted beers that made me go cross-eyed, but I’ve had some pretty good first attempts as well,” adds Gregor.

You can study beer your entire life

How do modern technologies affect the production of beer today?

Even small breweries have embraced automation. The entire process is entered into a computer, and the brewer only walks around the brewery, carrying a tablet and tapping buttons on the screen. The magic’s lost, I’m afraid, but that’s the way it is.

We no longer visit fully-automated breweries because there’s nothing to see for our students, apart from a lot of stainless steel. It’s better for them to learn to do the entire process manually; to stir the liquid with a stick to learn how the mash (crushed malt mixed with water) smells, what colour it is, and how its physical qualities change, e.g. viscosity. In the copper, the hopped wort “breaks”, meaning that the proteins in the hops containing polyphenolic substances condense and the wort gets purified. Suddenly, light passes through it differently, which is easy to see with the naked eye.

The Czechs say that beer is the best ion supply drink. Is this really true?

Non-alcoholic beer is, indeed. Beer combines hundreds of substances. From a chemical standpoint, it’s a comprehensive system even physical chemists deal with, and there’s still a lot of questions to answer, such as what causes the cloudiness, stamina, stability, colour, foam as well as what makes beer create strings of small bubbles on the walls of the glass. I often tell our students that some problems haven’t been sufficiently explained yet.

From this perspective, beer is simply brilliant. You can deal with one narrow path your entire life and you still won’t find all the explanations anyway.

So you’re not afraid of ever losing interest in beer…

Beer is a truly fantastic thing. Barley contains pretty much everything. You need only its grain to make malt, then some spices such as hops to prepare hopped wort, and after the fermentation you get a huge range of interesting flavour profiles. It’s not just about alcohol; the taste is a combination of the fullness of dextrin, oligosaccharides with a bit of acidity brought by yeast cells… What a brilliant drink!

Tomáš Gregor likes to have a good lager and some lighter beers in summer; he’s taken to sour beer containing lactic acid fermentation bacteria. However, despite his love for the beer, he doesn’t drink much – perhaps one decilitre a week. And even though he likes to motivate students to brew non-alcoholic beer, he’d leave alcohol in beer himself. “When drinking beer, you have to be reasonable, but lots of people have no idea what that even means.”