Leadership in times of crisis

Let’s start with the basics: what is leadership?

Let’s start with the basics: what is leadership?

Leadership is the art and craft of leading people.

Is it something you can learn or is it more of a talent, something a person either is or isn’t born with?

It’s the same as with the talent to sing – it’s important to have natural ability for it, but your ability to work it and develop usually determine success far more than the original material you start with.

And the same goes for leadership as well?

The analogy is similar, I think. Some people naturally and easily handle a lot of what is expected from them as leaders; their talent makes it easy for them. However, the demands of modern leadership in the 21st century are so huge that no leader can cover all that is expected from them. No matter how charismatic or predestined they are to do some things perfectly, there will still be things they need to learn and develop as they go. There will even be times when they’ll have to rely on their team to compensate for their inabilities. Let’s also keep in mind the unfortunate fact that today’s leaders are expected to have almost superhuman abilities.

So it was easier to be a manager 50 years ago?

Easier? Hard to say. It was definitely different, as leadership always reflects the times in which it exists. If, however, we agree that our world has grown more complex over time, then yes – today’s leadership is more difficult.

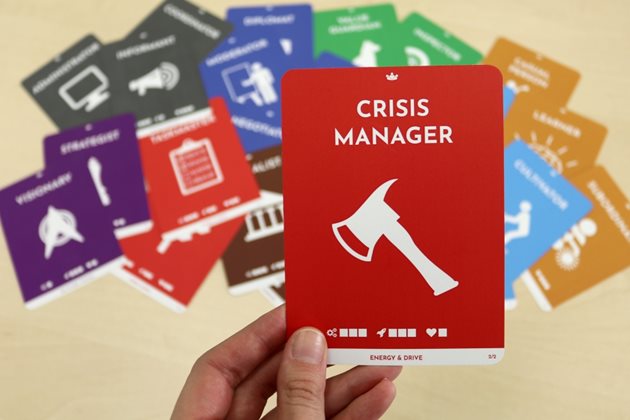

Beáta Holá is a psychologist and organisational designer focusing on holistic talent management. She’s been cooperating with the Court of Moravia for a long time, deals in leadership in-depth development and in everything related to relationships in company life. Beáta has designed and implemented specialized talent and development programs for international teams for dozens of organisations. She is the creator of the Leadership Cards methodology that enables a quick in-depth analysis of gaps in leadership and more efficient focus on development. In cooperation with Philip Zimbardo and Time Perspective Network, she’s been putting time perspective theory into practice as an approach to strengthening the resilience of individuals as well as organisations. Her mission is to help people in organisations find the best version of themselves.

When did leadership as such emerge in our society for the very first time?

It all started with the leadership in war and statesmanship, for example The Art of War by Sun Tzu is all about it. As a modern topic, leadership was born at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries when, following the Industrial Revolution and the birth of large companies, people began to discuss and explore how to manage others better. The first theories described a good leader as a robust man with a deep voice, manly and imposing; only gradually did it become clear that these rules don’t always apply, as now and then a short man turned out to be an excellent leader while a lot of large, imposing, men were worthless at it.

The search for what it really means to lead people then turned from external physical attributes to the inner characteristics of individuals. Conscientiousness, passion, analytical ability, and relationships started to be discussed, and things have been going in this direction ever since. YouTube is full of videos of people describing five, seven, or even twelve key qualities of a leader, so these efforts to capture the ideal mixture of qualities of people leading teams, which started around the 1920s, are still a common focus today.

And what is so complicated about these times that makes leading people so demanding?

They destroyed every leadership category that had been used up to this point. No category is large enough anymore and modern leaders are being pressured to master every aspect of it.

And this used to be different?

The borders used to be much clearer. In the 1940–1960s, amongst huge developments in statistics and data made collection, teams at two different American universities came up with identical results of leadership research. According to them, there are two axes that become apparent in leaders: result-oriented and people-oriented. This led to various combinations of leaders based on what they tend to do, called the theory of the managerial grid. Then another wave of research discovered that it’s not enough to know what qualities a leader has and how they are combined – it’s also necessary to look at what who the leader leads. It’s one thing to lead a capable but unwilling person, it’s another thing to lead an incapable but willing person, etc. And all this is situational leadership, which is a theory that emphasizes choosing your leadership style based on the people you lead. Transactional and transformational leaderships define the behaviour of transactional leaders, the ones who assign tasks, set the norms, appraise, criticize, enforce, and guard, and of transformational leaders who tell a strong story to describe a clear vision and lead by example.

What styles of leadership has the 21st century brought?

I consider versatile and servant leaderships to be among the most significant models of leadership of the 21st century. With versatile leadership, the leader is expected to handle the entire spectrum; they have to manage the operations as well as strategic thinking, juggle those tiny everyday tasks together with big things such as visions and strategies. They have to be able to lead in a directive way when necessary, but also withdraw and only offer support at other times. They have to have a solid grasp of the basics in all of these abilities in order to do a good job. What’s special and even adventurous about this leadership is that each of us has talents in only one part of the spectrum: you are either an operative or strategist. Either people or results. At the same time, we tend to overestimate the things we are good and downplay the things we aren’t. A good versatile leader has to realize what their natural talents are and what they undervalue. They have to be honest and admit their weaknesses and things they aren’t good at and work on them. How many of us can do this, though? How many of us can face their demons and look at their weaknesses in the eye? How many managers in exposed positions are receptive to being told “I’m not good at this – I can’t handle it.”? And this brings us to the main challenge of leadership in the 21st century.

What’s the main challenge of servant leadership?

Servant leadership as a theory claims that a company isn’t supposed to serve its leader and generate its salary and shares, but a leader exists to serve their company. They shouldn’t get in the way of natural processes in the company, but, at the same time, need to have a lot of skills, work in a conceptual way, heal the injuries of the organization, be able to work with the community, be a good manager as well as show true empathy… The aspects of what they have to handle are demanding and often contradictory, but it’s all based on the theory that a leader is here for the company to thrive while being “only” a servant.

Is there any difference between a leader in a company and a leader in politics?

For both it is absolutely essential to understand which role the entity they are leading expects from them. In those positions, we aren’t paid for who we are or for showing our personalities, faces, and talents to the world – we are paid for fulfilling our roles. And not just one, but five, ten, even fifteen roles that we have to keep adjusting. A good leader has to know which roles are expected from them and how to fulfil them. The roles a politician is supposed to play and how to differ from those played by a manager, yet they are both expected to fulfil those roles, and there’s no getting around it.

A leader is paid for fulfilling some roles?

Hearing this takes a lot of managers by surprise, too. They aren’t paid for being a smart analyst who understands microscopes. Their technical knowledge in the discipline is only about 10% of it and the rest is about a number of other roles that – put together – got them hired. When I discuss this with leaders, it’s always interesting to witness the moment of honest surprise on their faces when they realize which roles are key for them. It’s true, though – the best leaders are the best because they can practice a lot of self-reflection, are aware of their roles and can switch among them, are flexible, and are able to adjust the roles they play in order to fit the current situation.

What demands has the coronavirus crisis brought for leaders?

The entire situation can be summed up like this: all you’ve been practising for years when working on your leadership is now at hand for you to apply. This is when you find out just how well you know your people, how well you’ve managed analytical tools needed in leadership as well as tools to manage your business. If you’ve invested the time into these areas when times were good, you have a lot more to work with when things get worse. Strong knowledge of your people will often guide the way, perhaps even to developing new teams and products based on the strengths of your people.

What should leaders avoid these days?

One of the rules for times of crisis says that you don’t want people to learn a lot of new things because it goes against human nature to return to the familiar during times of stress. We revert to crisis mode and rely solely on what we feel most comfortable doing. A leader should focus on utilizing only the talents where their people excel. This, however, requires a deep knowledge of each person’s strengths and weaknesses. This is absolutely essential because if you don’t know your people, you can’t correctly appraise, criticise, develop, promote them, and so on.

Is it possible to somehow sum up what leaders are expected to do right now?

Don’t fall apart. And to show some hope. People need to see some resilience, such as “I know what I’m supposed to do, and we’ll succeed.”

Like the British queen – “We will succeed!”

Exactly. And the second item on the list of what a leader is expected to show these days is adaptability. According to research by Deloitte, this is the main competency organisations expect from their people in 2020. Leaders have to be extremely adaptable, agile, and innovative. They need to be able to quickly find out what their customers, mankind, and the whole world need at the moment, and they have to innovate and come up with a way to save their business. Risk assessment is another thing a good leader needs to handle well these days – to be careful when running the company, to be smart when deciding what to continue with and where to redirect their energy. And last but not least, managers are expected to focus on their people, to be there for them, inform and listen to them, and make sure the atmosphere in the team remains healthy. Simply put, to keep the team viable during the crisis.

Is there anything inspiring about this crisis in terms of leadership?

Everybody has been saying “solidarity” over and over again, and for me this is a strong message to leaders of the world: don’t try to manage everything yourselves. Surround yourselves with other leaders who are strong right where you are weaker. Find a safe place where you can be vulnerable. And find someone brave enough to tell you that you’ve screwed up. Keep track of all the aspects of crisis leadership, base your next steps for this period on it, and – mainly – communicate.

In regular times, when everything gets back in place, as we hope, what do you think leaders should take from this crisis and continue to apply to the work they do?

First, they should be aware of the fact that nobody can do everything on their own. Create a strong team with members that complement, rely on, and trust one another. You need to be an actual team, not just a group of people who share office space.

Second, don’t underestimate your own needs to work on yourself, both as a leader and, more generally, as a person. Leadership starts inside, after all. You should try out any new concept on yourself first. Be your own guinea pig. Companies often wave this off, saying “Skip this part, let’s get down to how to lead people. We need results, so let’s criticise, motivate, and assess, and let’s do it quickly!” However, what you invest into yourself, into the leader inside, is that effort that pays dividends later on when leading individuals and companies. And in times of crisis, it’ll make you stronger and radiate peace and stability, as this healthy way you take care of yourself will make you resilient, peaceful, and powerful. The “peaceful power” is what helps make major decisions, such as what to cut down, where to redirect sources, whom to support, and what to communicate.

And third thing, rather personal. I am hoping this crisis will contribute to the end of what I call catalogue trainings, such as “Time Management 1”, quickly followed by “Time Management 2” that people in organisations approach like finished “products” and attend with the expectation that ten percent of the know-how that the instructor sprays on them will somehow stick, like a farmer dusting crops. This dinosaur of a mindset no longer works and has to go extinct, and I am hoping this crisis will shake things up enough that it finally dies. Education needs to be a living, organic thing that reacts to the real needs of people, and it needs to be microscopic – giving me the tools I need to learn a tiny thing every single week, to work on abandoning a bad habit, and every month polish some aspect of a role the company expects me to play. Microeducation tailored to my needs. And this is where the development market has to learn to help companies; to come up with solutions tailored to their needs, be there with them, and guide them.

Going through all that’s been said here about leadership, the very last question comes into my mind: do you think we ask too much of leaders today?

This brings us back to versatile leadership, which says “You should be able to handle almost everything!” Well, it’s no piece of cake to be a leader. And it’s not a sprint – it’s a marathon. From the perspective of servant or versatile leadership, becoming a good leader is a life-long mission. Sometimes a 35-year old person tells me that they are an excellent leader, and I always reply: “I’m really looking forward to seeing this, because if it’s true, I’ll kneel down right in front of you to worship the leadership messiah.” Much more often, this person simply doesn’t see a lot of things. And once they see them, they’ll understand that there’s still so much to do for the rest of their career. But it’s alright! This doesn’t apply to leaders only; being a good leader is just as hard as being a good parent, a good doctor, a good priest, a good person… Simply put, being good at anything requires us to never stop working on ourselves.